William Tyndale - God’s Providence with the English Bible

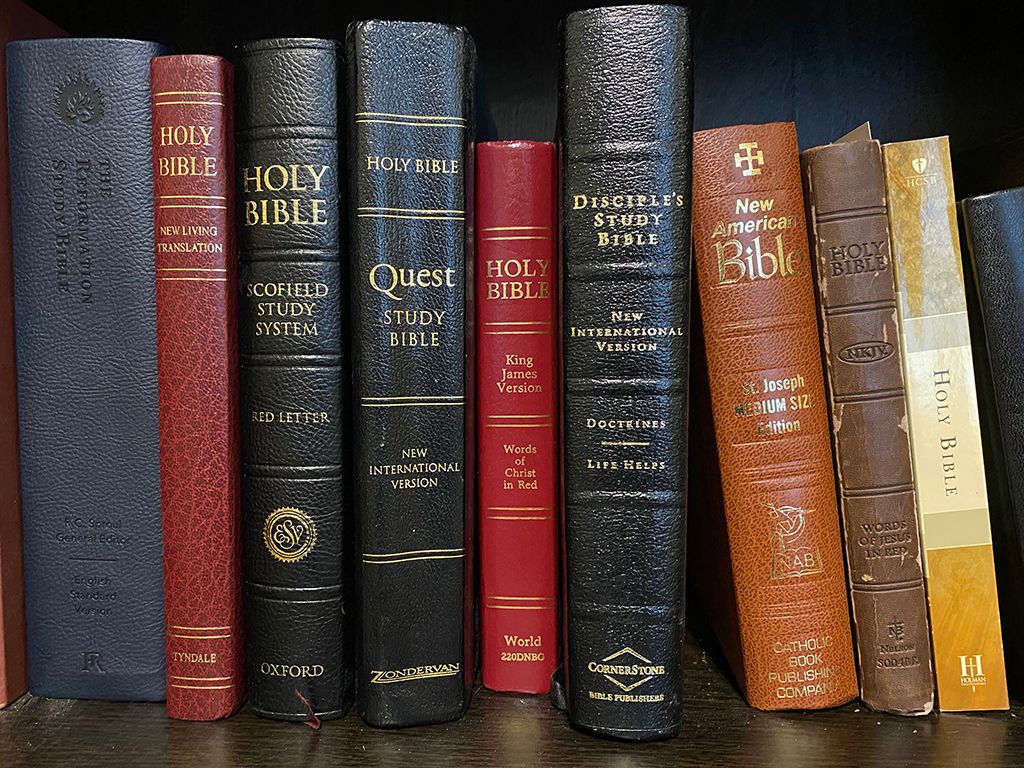

English-speaking Christians have many options when it comes to finding a Bible translation. The Bible study website BibleGateway.com currently offers more than 60 different English translations, from the 21st Century King James Version to Young’s Literal Translation.

With so many translations available, it is easy to take it for granted that we have an English Bible to read. It has not always been this way, though. In fact, there was a time when translating or reading the Bible in English was a crime punishable by death and many died for translating, distributing, and defending the right to own an English Bible.

God used many people to ensure the translation and distribution of the Bible in English. In this article, we will focus primarily on William Tyndale. He was martyred for his devotion to translating the Bible into English.

The Bible Before English

The Bible was originally written in two primary languages: the Old Testament in Hebrew and the New Testament in Greek. Both contain a small amount of Aramaic. In the late 300s, the church father Jerome wrote a Latin version of the Bible based on the existing Old Latin translation of the time called the Vulgate.

The writing of Jerome’s translation was commissioned by Pope Damasus I in 382 and completed in the early 400s and eventually became widely accepted by the Roman Catholic Church. At the Council of Trent in 1546, it became the authorized Bible of the Roman Catholic Church and, with minor updates over time, it remains so today. [1]

The English Bible Before William Tyndale

In England, translations of the Bible began as early as the 600s into Anglo-Saxon and Old English, the two main predecessors to the modern English language. These translations were based on the Vulgate and were not complete translations of the Bible, but only sections such as the Psalms and Ten Commandments. [2]

The first effort to translate the full Bible into English was done by John Wycliffe. Wycliffe was born around 1329 in Yorkshire in Northern England. He eventually became a Roman Catholic Priest and theologian, but gradually became an opponent of the Roman Catholic Church. One of his primary issues was the church’s requirement to preach only in Latin because by this time in England, only the educated understood Latin.

Wycliffe was passionate for the common English person to hear the word of God preached in English and for the Bible to be translated and distributed in English as well. He began the project of translating the entire Bible into English based on the Vulgate in the 1380s. [3]

Wycliffe died of natural causes, but his bones were dug up after his death and burned as an act to condemn him as a heretic for his teachings and his efforts to translate the Bible into English.

Erasmus

Before moving to William Tyndale, we must mention Erasmus of Rotterdam (Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus). In 1516, Erasmus published his Greek translation of the New Testament, using the most reliable Greek manuscripts available. This allowed those who understood Greek to read the New Testament as close as possible to its original form. This translation also included a parallel new translation in Latin which refined Jerome’s translation because of improvements in understanding the Greek of Jesus’ time.

Erasmus’ translation caused controversy in the leadership of the Catholic Church at that time as his corrections to Jerome’s text were considered heretical, as if Erasmus was correcting God rather than the errors of a man.

William Tyndale

William Tyndale was born between 1490-1494 in Gloucestershire in Southwest England. He attended Oxford University and in addition to English, became fluent in French, Greek, Hebrew, German, Italian, Latin, and Spanish. [4] It was while he was at Oxford that he first read the Erasmus translation of the New Testament. He was initially drawn to it for academic reasons, but God used the text itself to convert him. After becoming a Christian, he began lecturing and preaching the authority of Scripture above tradition of men.

In 1522, he returned to Gloucestershire to the manor of the Walsh family as the chaplain and tutor of the children. While there, he often debated with the Roman Catholic clergy that would come often to the home. Tyndale himself wrote about many of the discussions he had around the dinner table with the theologians. For example, he wrote of a priest who said, “nothing is obscure to us (the priests); it is we who give the Scriptures, and we who explain them to you.” Tyndale responded to him, “do you know who taught the eagles to spy out their prey? Well, that same God teaches his hungry children to spy out their Father in his word. Christ’s elect spy out their Lord, and trace out the path of his feet, and follow.” [5]

In addition to preaching at the small church on the Walsh manor, Tyndale also preached in neighboring towns and villages, preaching the truth of grace through faith alone. The Catholic Church soon heard and would come into the towns in which Tyndale preached, labeling him a heretic, and threatening to expel anyone who would listen to him. [6] This first laid the thought in his head for an English bible. He believed that if English Christians could read the Bible for themselves, they would become strong in the faith and withstand the false teachings of the day. [7]

Tyndale eventually realized that it was not safe for him or the Walsh family for him to stay on their manor. He left to concentrate all his efforts on writing his English translation of the New Testament based on the Greek. Since he was not safe anywhere on the island of Great Britain, he was led to flee to Germany in 1524. [8]

The first edition of his translation of the New Testament was finished in 1526 and was smuggled from the European continent into England. The English New Testament quickly spread among believers, but it was not welcomed by the church or the King. [9] In October of that year, Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall condemned the book and publicly burned copies of the book as a warning to bookstore owners who sold it. In January 1529, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey officially labelled Tyndale a heretic. [10]

Tyndale moved between several cities in Europe to stay hidden. During this time, he revised his New Testament translation, drafted translations of several books of the Old Testament, and wrote several other books and treatises. In all, an estimated 16,000 copies of his English translation were printed in Germany and smuggled into England.

Tyndale was eventually betrayed and captured by authorities of the Holy Roman Empire in 1536 in Antwerp, Belgium. He was imprisoned, tried, and convicted as a heretic for preaching the Gospel and printing the Bible in English. In October of 1536, he was strangled to death and his dead body was then burned. The last words he reportedly spoke were, “Lord! Open the King of England’s eyes!” [11]

After Tyndale

We can only appreciate fully the contribution of William Tyndale by looking at the impact of his work after his martyrdom. From 1535-39, several revisions were made to Tyndale’s work, the last of which became known as the Great Bible. This translation was Tyndale’s full New Testament plus his published Pentateuch (Genesis through Deuteronomy). The rest was largely his previously unpublished Old Testament. The Great Bible is significant because it was authorized by King Henry VIII and was read in the Church of England services, an answer to the cry of Tyndale’s dying words.

This translation itself was revised in 1582 by bishops from the Church of England and came to be known as the Bishop’s Bible.

In 1604, King James I sponsored a new translation by many scholars of the day. They revised the Bishop’s Bible considering new understanding of the original languages. The translation was finished in 1611 and eventually became known as the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible.

Even though the KJV was a new translation at the time, it owes much to William Tyndale. In fact, according to research done by scholars such as Naomi Tadmor, Tyndale’s words make up 83% of the KJV New Testament and the 76% of the Old Testament. [12] The KJV soon became the most popular English translation and remained until the mid-1980s.

Today

There have been many revisions to the KJV such as the Revised Version, the American Standard Version, the Revised Standard Version, and the English Standard Version. These translations are all descendants of Tyndale’s work and sacrifice of almost 500 years ago. Even English translations that do not directly descend from Tyndale such as the New International Version owe much to his dedication and sacrifice.

Let us be thankful to God for His grace in allowing people such as William Tyndale to labor to produce a Bible so we as English-speaking people can hear and believe (Romans 10:14).

Miller, J. E. (2016). Vulgate. In J. D. Barry, D. Bomar, D. R. Brown, R. Klippenstein, D. Mangum, C. Sinclair Wolcott, L. Wentz, E. Ritzema, & W. Widder (Eds.), The Lexham Bible Dictionary. Lexham Press. ↩︎

Greenspoon, L. J. (2016). Bible, English Versions of the. In J. D. Barry, D. Bomar, D. R. Brown, R. Klippenstein, D. Mangum, C. Sinclair Wolcott, L. Wentz, E. Ritzema, & W. Widder (Eds.), The Lexham Bible Dictionary. Lexham Press. ↩︎

Ibid ↩︎

Daniell, David (1994), William Tyndale: A Biography. New Haven, CT & London: Yale University Press. ↩︎

D’Aubigne, J.H. Merle (2015) The Reformation in England, Volume 1. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust. ↩︎

Ibid ↩︎

Ibid ↩︎

Ibid ↩︎

Lawson, Steven J. (2015), The Daring Mission of William Tyndale. Sanford, FL: Reformation Trust Publishing. ↩︎

Ibid ↩︎

Ibid ↩︎

Tadmor, Naomi (2010), The Social Universe of the English Bible: Scripture, Society, and Culture in Early Modern England. Cambridge: UP. ↩︎